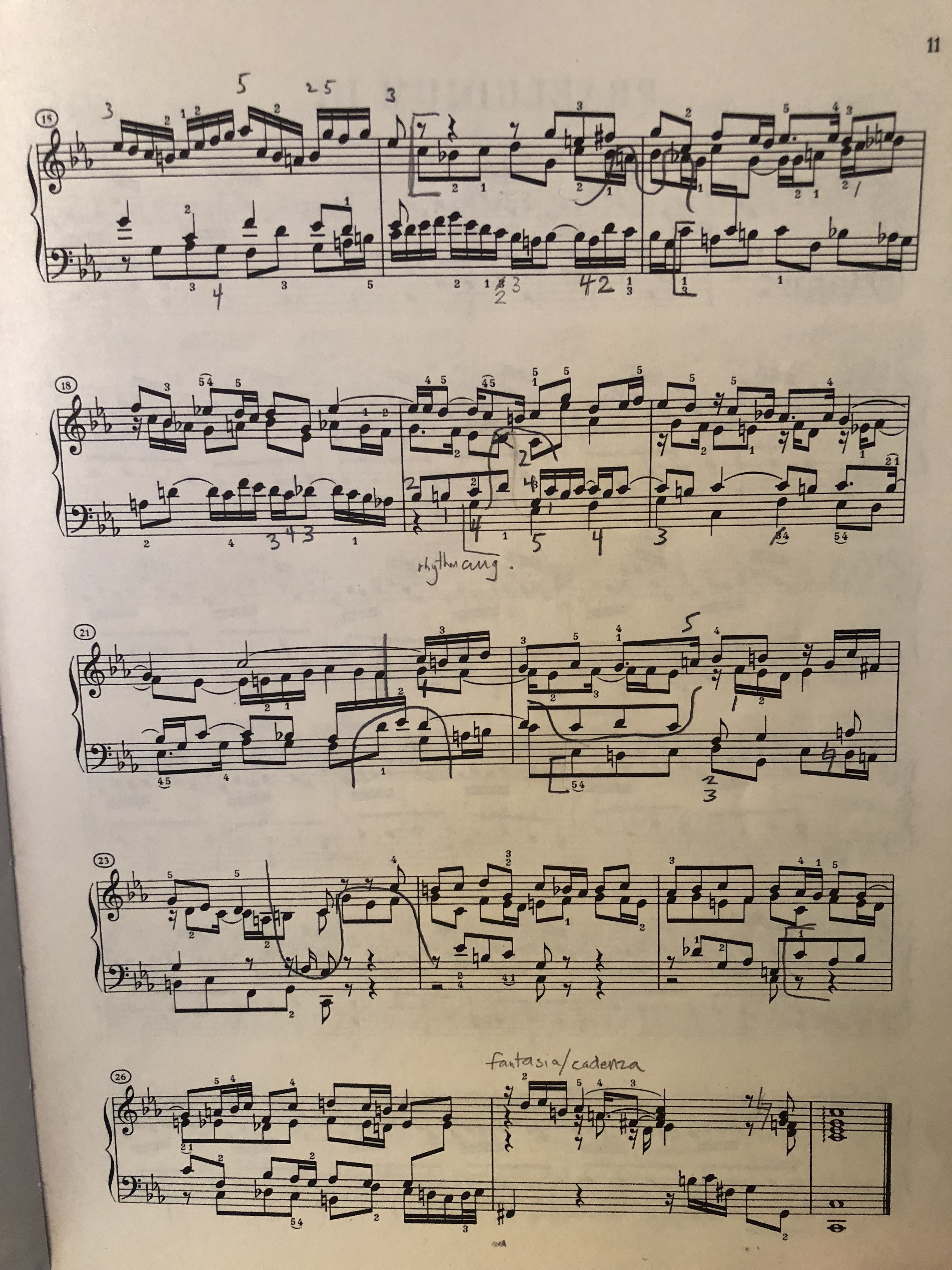

- Because I’m trying to learn each movement relatively quickly (one prelude and fugue per week is doable, though not at performance-level), I have one initial listen-through with a random recording and will begin noting the architecture of certain lines. In my score, I draw square brackets around fugal subject and rounded brackets (parenthesis) around lines that are strongly derived from the subject. This immediately draws my attention during a subsequent play-through. Although I could make the same markings by doing score study or by playing each voice alone, the process is speedier if I pencil in my “map” of fugal subjects while listening to Schiff, Gould, or Barenboim.

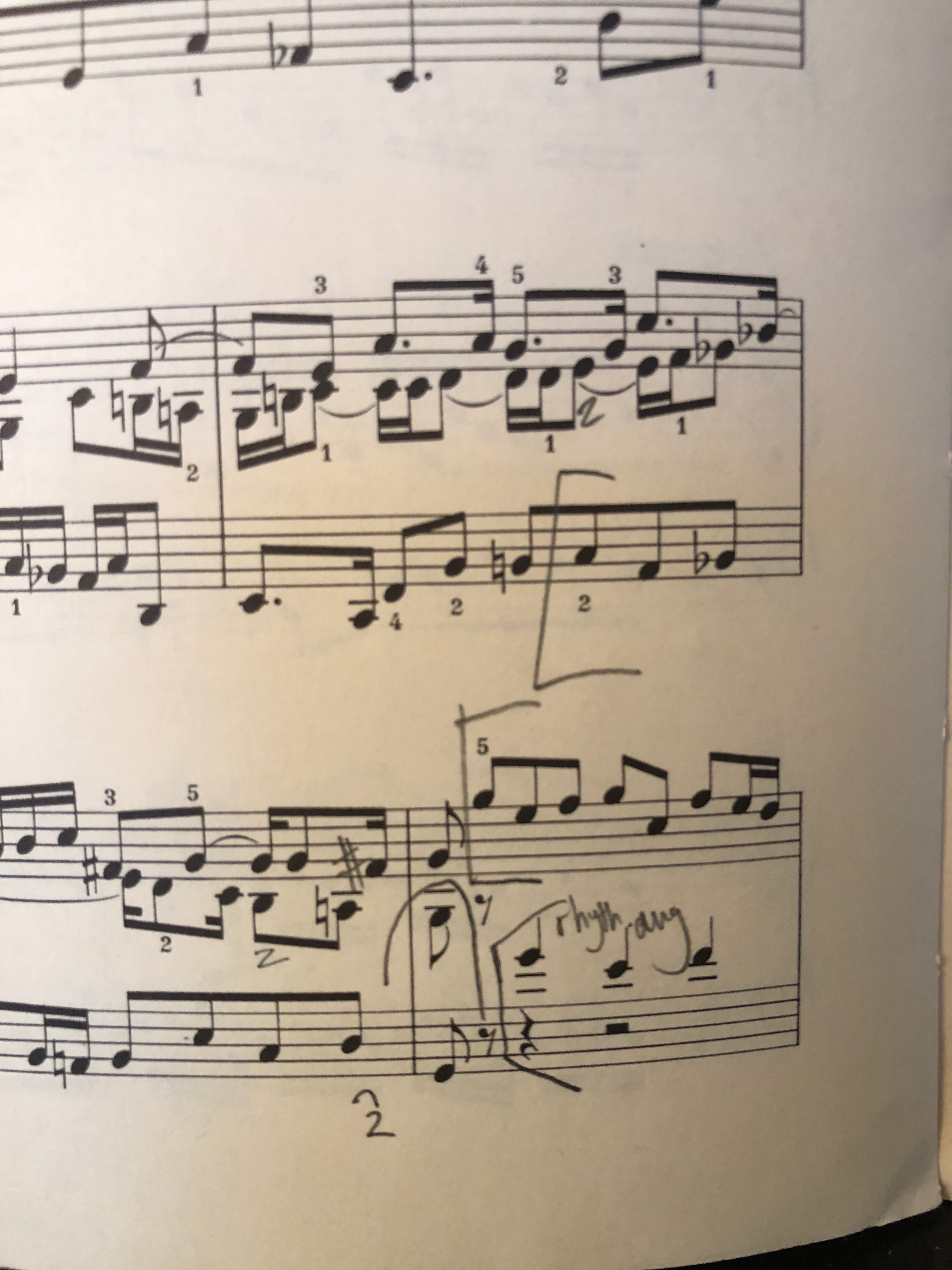

A couple of square brackets for subject entrances in the C minor fugue - I learn large sections (half a page at a time, usually) with just a single hand. Honestly, I find it a bit pointless to learn each voice separately, as it is not conducive to planning my fingerings. I need as much context as possible to start writing in fingerings, and usually the two voices in a single hand are enough. There are certain moments, though, when even that isn’t enough context (moments when one hand has to dip into the other clef to play three voices), but planning that comes later in my process. I’m using the Henle Edition of Book 2, so I do attempt its editor’s fingering recommendations first. Sometimes they work, sometimes they just need small amends, and sometimes I don’t find their suggestion helpful at all. I try to be extremely conscious of the fingering markings I put into the score, which usually takes a few focused hours for a single page. I’ll cross out the editor’s suggestions so that they don’t mingle with my own; I’ll circle fingerings that are very important––the fugues are puzzle-like, so it helps to know those miss-it-and-you’ll-be-guaranteed-to-stop moments of getting the right finger; I’ll seek out very specific, quick moments that I’m unsure of which finger to use, which usually results in me writing in more fingering numbers than I need.

- Repeat step two with the opposite hand. Usually the other hand goes quicker, as it may only have one voice for that half-page of music.

- Playing extremely slow and legato, I put the hands together. I’m most concerned that I’m consistent with the fingerings I’ve written in, almost more so than correct notes. However, feeling the intervals between each finger is also extremely important in the process, so (obviously) it helps to play the correct notes. With that said, there are times I’ll play the wrong note, but with the correct finger. I’ll simply make a mental note and count that play-through as a success. Building a consistent fingering is ideal. I also make a mental note of parallel fingerings––moments when, usually on a larger beat, the same finger plays in both hands. Thumbs together! I think, and usually draw a tall circle around those instances.

- After I get the tempo at more than a snail’s pace, I’ll start referring back to the notations I’ve made in the first step of the process (the “map” of brackets). Always paying attention to fingering, I’ll start bringing out the fugal subject. I’m really just hoping to learn the fugue “straight” first, even if it may sound pedantic or square.

- If time permits, I’ll play each phrase with a different voice brought out and make some interpretative decisions based on what I like. Based on the fugue’s form, I’ll also note points that a primary voice isn’t necessarily important (sequential patterns between voices).

- After I’m able to play through the entire thing (under tempo) and feel rather comfortable, I go back to a couple of recordings for ideas. Of course, not for the purpose of copying another pianist, but just for inspiration on how to make it more interesting with different voicing or ornamentation. This is also the point that I experiment with different articulations and touches. For example, in the C minor fugue, I will play passages staccato just for practicing sake. In the faster C Major fugue (Book 2, No. 1), however, I may start practicing staccato because I think it may be the correct detached touch needed for the style––I begin practicing for performance, per se.

In a future blog post, I’ll discuss those instances when a hand has to dip into the other clef (either to play three voices at once, or just general hand substitution). In the image above, those moments––commonplace in Bach––are shown with a long, curved or swooping line.